How can we bring to the open and address the personal, institutional and political values tensions manifesting in our workplaces ?

Vic team writes about the values tensions observed in academia. Below is a re-post of the original article posted in the ACM interaction magazine blog on 25th June 2018 http://bit.ly/2KlV4l2

Values Tensions in Academia: an Exploration Within the HCI Community

February and March 2018 saw the largest ever industrial action in the UK’s higher education sector. Whilst the cause of the strike was changes to the USS pension scheme, the picket lines were sites for conversations about many other issues within academia. Whether it was dissatisfaction with the corporatisation of universities, the precarious working conditions of early career researchers, or over-work, there was a clear sense that the values held by those striking were in sharp contrast with the realities of university life. The ‘depth of feeling’ was often bitter and angry, and the frustration with today’s higher education system palpable.

Whilst many reported a loss of trust in the system and in their own institutions, fresh hope and renewed energy came from activities such as the teach outs, open teaching and discussion sessions outside the campus. These initiatives offered concrete examples of different ways of engaging with learning and research across disciplines and roles; ideas were proliferating like a “thousand butterflies”. Many now feel that very broad bridges are needed to start filling the values gap that has manifested itself so clearly during the strikes; as Prof Stephen Toope, Cambridge University Vice Chancellor, puts it “the focus should be on what values our society expects to see reflected in our universities, not just value for money”.

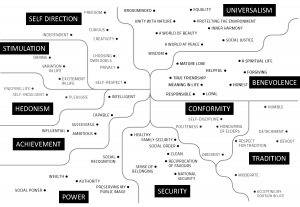

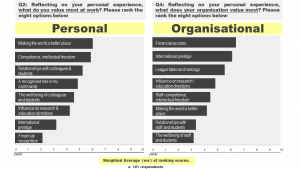

Overall, most respondents felt their values matched their institution’s to some extent (57% of the respondents). However, almost a third reported that their values either did not match (26.5%) or did not match at all (6%) those of their Institution. The survey also asked respondents to rank a list of options according to which were most highly valued in their work; this is where the values tensions became manifest. As the bar charts in Figure 3 show, the top three most highly ranked options were ‘making the world a better place’; ‘competence and intellectual independence’; and ‘relationships with colleagues, students and partners’. These statements were designed to represent Universalism, Self-Direction, and Benevolence in Schwartz’s values model and followed previous research guidelines. Positive societal impact, autonomy of thought and meaningful relationships were thus the things that these computing professionals most valued about their work. By contrast, ‘financial recognition’ (Power) was the least valued.

They felt that their institution most highly valued ‘financial success’, ‘international prestige’ and ‘league tables/rankings’. All these three options belong to the Power values group. By contrast, the bottom three options were ‘making the world a better place through work, research and teaching’, ‘staff relationships with colleagues, students and research/work partners’, and ‘supporting the well-being of staff, students and partners’. Thus, the things that the respondents most valued – with the exception of intellectual autonomy – were seen to not be highly valued by their institutions.

The implications of this friction between personal and institutional values cannot be ignored and deserve further attention. Even if this tension may be, to a certain extent, ‘perceived’ or ‘inevitable’ or both, the widening of the values gap may have problematic consequences. For example, recent research and extensive media coverage worldwide suggest high levels of stress and mental health problems within academia. However, the emphasis of these studies is often on the temporal and mental burdens created by the demands of the workplace, and the need for raising awareness and promoting self-care (i.e. through apps and physical activity).

Something that isn’t often talked about is whether the values tensions may have health and well-being implications, and the need for digging deep into the root causes of these tensions before defaulting to self-care coping mechanisms. This may be particularly the case in the HCI community, as many of us not only grapple with personal challenges, but also with the challenges of a much deeper and broader “existential crisis”. This is especially important because much of HCI research focuses on designing and developing digital technologies that can change people’s lives rather than examining how digital technologies come to life. We need to look into values tensions not only for the end-users and broader stakeholders, but for us – researchers, educators, designers, and developers.

To this end, we argue that a better understanding of values is needed, especially when it comes to computing technologies. From a research and practice perspective, this means to build on, but also go beyond, the substantial corpus of research in Ethics and the well-established research field of values sensitive design (VSD).

Our question for the HCI and broader computing community is how to bring to the open the personal, institutional, and political values tensions manifesting in our workplaces (i.e. academia, research). In other words, how can we support the next generation of computing professionals with the deliberative, technical, and critical skills necessary to tell the difference between what is worth pursuing from what is potentially harmful to self and society? And how can we create and support institutions where this civic purpose can flourish?

Thank you!

This work is part-funded by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council UK (Grant number: EP/R009600/1). Warm thanks go to our project partners and to the CHI2017 ViC workshop participants, who have jointly shaped the vision and direction of this research. A special mention also goes to the thousands of conversations had with colleagues and students within our School and across campus. More information about ViC and related work can be found at www.valuesincomputing.org